How Kenya's poisoned, thorny nightmare began as an optimistic tree-planting initiative

John Lmakato has spent his whole life in Lerata, a community in Samburu County, northern Kenya, which is tucked away at the base of Mount Ololokwe.

There used to be no trees on this site. He claims that livestock wandered freely and that the rangelands were completely covered in grass. Three years ago, Lmakato lost 193 cattle that had wandered into a conservation area in Laikipia, which is infamous for the conflicts between commercial ranchers and Indigenous pastoralists over land access. Previously, his cattle roamed freely in search of forage. He claims that some of his cows were shot dead. "Humans were killed." Lmakato used to own 200 cattle, but now he just has seven.

The mathenge, also known as the mesquite shrub (Neltuma juliflora, originally classed as Prosopis juliflora) in Kenya, was one of the primary causes of the livestock of Lmakato, 48, crossing over into the conservation area. Cattle must travel farther to graze because inedible mathenge trees dominate the grassland terrain. Mathenge is a South American plant that was introduced in 1948 and expanded over east Africa in the 1970s.

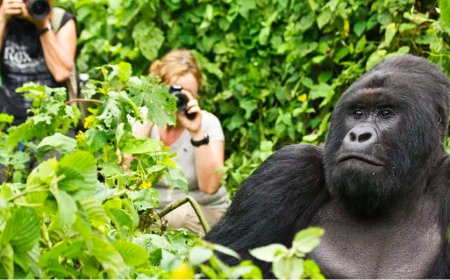

In addition to serving as a source of fuel and animal feed, it was thought to have the potential to mitigate the effects of creeping desertification, minimize soil erosion in arid regions, and provide tree cover. Its cultivation was strongly promoted in Kenya by the government and the UN Food and Agricultural Organization. It soon turned into a nightmare as the plant grew. One of the deadliest invasive flower species in the world today is a closely related species. Since its inception, mathenge has proliferated throughout the nation, putting almost three-quarters of Kenya in danger of invasion. It has taken over wide areas of the country's semi-arid and arid regions, choking out extensive rangelands and using its deep roots to extract moisture from the soil.

It has encroached across an estimated 2 million hectares (7,700 sq miles), according to the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (Kefri). It is expanding up to 15% year, according to Kefri scientists. We will never be able to eradicate the plant. We must therefore exercise control over it. Environmental officer Ramadhan Golicha Its detrimental consequences sparked a lawsuit against the Kenyan government in 2006 after residents of Baringo, one of the most affected areas in the nation, filed a petition for damages from the introduced mathenge trees. The government lost the case in court.

“The spread is so fast that it has caused entire communities to be displaced, schools to close, and even disrupted river flows, as the plant blocks watercourses – contributing to flooding and displacement,” says Davis Ikiror, Kenya-Somalia country director for Vétérinaires Sans Frontières (VSF) Suisse, an organisation that has worked in Kenya for more than two decades.

In Samburu county, where more than 60% of the population are pastoralists and 30% mix herding with small-scale farming, livestock is a lifeline. Some animals die from mathenge toxicity after ingesting it in large amounts. While grazing, the plant’s tough thorns injure the animals by lodging in their feet and its sweet pods – high in sugar – cause dental decay and the loss of teeth among the animals.

The dark canopy and delayed water flow are perfect breeding grounds for mosquitoes, which exacerbate the spread of Rift Valley disease, malaria, and kala-azar, or leishmaniasis, which is spread by sandflies. The biodiversity has suffered greatly as a result of the plant's chokehold. According to Douglas Machuchu, project manager at VSF Suisse, once it is seeded, it creates a dense canopy that blocks out light, preventing other plants from developing. The shrub needs to be controlled in order to preserve entire ecosystems. "Nothing grows underneath where mathenge grows properly," he claims. For additional nature coverage, follow the Guardian app's biodiversity correspondents Patrick Greenfield and Phoebe Weston, and find more age of extinction coverage here.

Kinyarwanda

Kinyarwanda

English

English

Swahili

Swahili